Why most explanations overload the brain (and how to stop doing that)

Everyone is unique, but when it comes to learning, our similarities outweigh our differences.

We all have brains. And all brains work in similar ways. To understand how, let’s take a brief trip into the world of cognitive science. We’ll look at two frameworks that help understand what’s going on in any learner’s mind. Without them, you’ll be shooting in the dark. With them, all the explanation tools we’ve encountered in my previous articles will fall into place.

Working Memory

You’ve got 3 seconds to memorise the following letters:

HTENNMKSEMAJEROOE

Time’s up. Test yourself.

How many letters did you get?

All of them?

Probably not. Unless you were using some advanced memory techniques, which would be pretty tricky to apply within 3 seconds!

Now try again:

JAMES KENNETH MOORE

The content is identical but the difficulty is gone. You don’t have a bigger brain than you did three seconds ago, so what changed?

Simple: the presentation. The information is now organised in a way that your mind can handle effortlessly.

This illustrates the essential constraint of explanations: the narrowness of working memory.

Working memory is your brain’s sketchpad, the space where you hold and manipulate information in real time. Unfortunately, working memory is limited. Most estimates suggest it can hold somewhere between four and seven items at once. Present too much information too quickly, it overflows. You feel confused, fatigued, or like you “just don’t get it.” Yet the problem is almost always upstream: the explanation was not shaped to fit what the brain can hold.

Long-term memory, in contrast, is vast. As we learn, we move information from our temporary, limited working memory to the stable, infinite long-term memory. What makes the art of explanation challenging is that we can’t expand working memory – it’s fixed. We can, however, change what counts as a single item, by relying on what’s already stored in long-term memory.

When you read JAMES KENNETH MOORE, your brain treats it as three words, not 17 letters. That act – recognising structure and compressing it into a single mental packet – is called chunking.

A good explanation organises information into manageable chunks that are already embedded in long-term memory. It guides attention, highlights structure, and builds the very chunks that learners need to internalise. When done well, it doesn’t merely inform; it alters the very structure of the brain.

Cognitive Load Theory

Working memory is tightly linked to another simple framework that’ll help you understand why the explanation tools we’ve encountered in previous articles work. It’s called cognitive load theory.

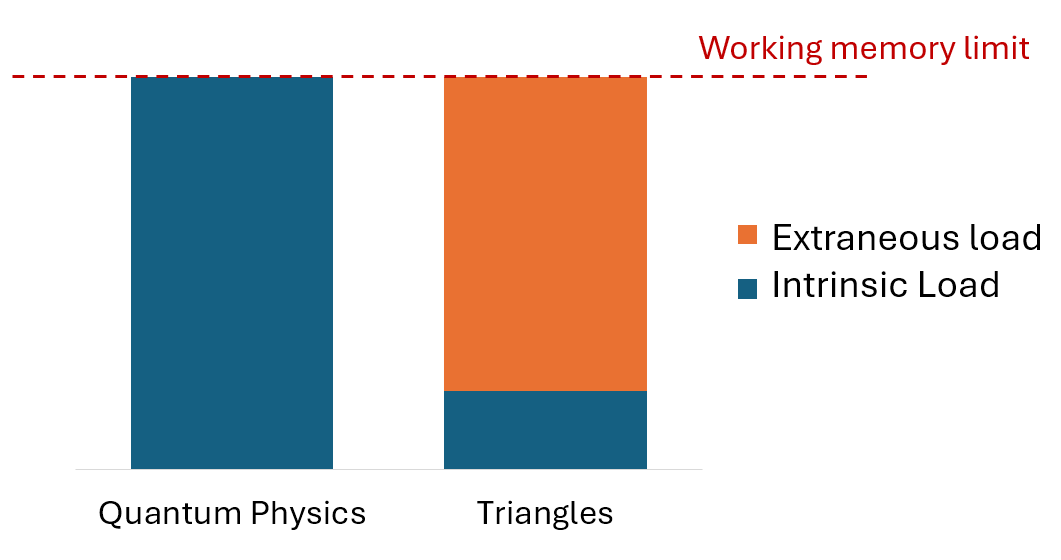

The premise is simple. Anything we try to learn requires mental effort – also known as cognitive load. And there are two types of cognitive load that are particularly relevant to us as explainers: intrinsic and extraneous. Intrinsic cognitive load is the mental effort that’s inherent to what you’re learning. Extraneous is anything irrelevant that makes learning harder.

An example. You’re watching a video about quantum physics. It’s pretty complex, and you have to concentrate pretty hard to understand. It’s got high intrinsic cognitive load.

You switch to a video about different types of triangles. It’s simpler, so it’s got lower intrinsic cognitive load. But then your brother comes in and starts prodding you while you’re trying to watch. He just increased the extraneous cognitive load. And now you can’t even absorb this simple information!

Both scenarios are overwhelming, and breach your working memory capacity. But in the quantum physics example you’re learning more, because you’re devoting a greater proportion of your working memory to what’s important: the intrinsic cognitive load.

Cognitive load theory was developed by Australian psychologist John Sweller. It’s been described as “the single most important thing for teachers to know”, by prominent educator Dylan Wiliam. But it doesn’t just apply to teaching. Any form of communication – a talk, a PowerPoint presentation, a video – would benefit from being passed through the lens of cognitive load theory.

As explainers, it’s our job to ensure our audience’s precious working memory is devoted entirely to what’s essential – the intrinsic cognitive load of what we’re trying to explain. That means eliminating extraneous cognitive load in all its forms: unnecessary details, busy slides, irrelevant tangents.

Think of it like this. You have a bucket filled with a mixture of green marbles and red marbles. A good explainer picks out the red marbles, before handing their audience only the green ones, one at a time. A bad explainer dumps the whole bucket over their head at once.

So, how do we apply all this theory to tailor an explanation to our specific audience? I’ll explore that in more detail next time. But for now, I’ll leave you with this: start where they are, not where you happen to be. Consider what’s already chunked in their long-term memory. Eliminate as much extraneous load as possible. And feed them one atom of the explanation at a time – waiting for them to absorb it, before moving on – so they stay with you on the journey.